A lot of focus in conservation and ecology is around the concept of a baseline. I spoke about them in my previous blog, reflecting on how we can look at trends in the past as points of comparison for the current state of the natural world and the number and variety of life forms that exist within it. That being said, there are many facets to the term, and the more you think about it, the easier it is to pick apart. My next few blogs will be reflecting on this.

Space4Nature: What's in a baseline? (Part 1)

Meadow pipit by Tom Marshall

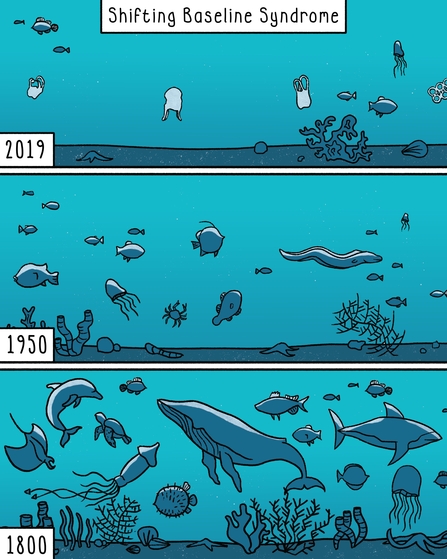

The term “shifting baseline” is often brought up in reference to climate change. It expresses the idea that because the environment has changed so drastically, the baseline we are realistically able to get back to is far away from the baseline we’d ideally like to aim for. This is a more complex discussion, which lead us into other ecological theories such as alternate stable states, so what I want to focus on for this blog is the psychological side to shifting baselines, or the “syndrome”.

Shifting Baseline Syndrome is a shift in perception of what normal is understood to be; in our case, a shift in what we think a healthy ecosystem should look like. The term was originally coined in 1995 by a fisheries scientist called David Pauly. Pauly observed how successive generations of fisheries staff had different reference points for fish populations, and how depleted (or not) they should realistically be. Because their individual reference points were largely based on the state of the fishery at the start of their careers, workers developed increasingly lower standards for fish populations. As global fish populations continued to decline as a result of pollution, overfishing and other human influences, each new generation of fisheries scientists had increasingly worse conditions to dictate their perceptions of normal.

Illustration by Cameron Shepherd

This phenomenon has been described as generational amnesia – a fantastic term. We have all heard stories of (or perhaps remember ourselves!) how there used to be so many more birds in our gardens, more greenery in the countryside and more wildlife all around us. Another common reference point is the number of deceased insects splatted on our car windshields. Kent Wildlife and Buglife have run a Splatometer study since 2004 and recorded a 59% decrease in the number of insects ‘splatted’ on people’s vehicles nationally. So clearly those reminiscers are telling us something real. While some of those reading this might remember driving with heavily splatted windscreens, as someone who only started driving in 2010 I have never really experienced this. My reference point for insect populations is likely to be massively different than that of my parents, and will probably be massively different from that of future drivers. So, what does that mean for nature’s recovery?

Well, research has shown that Shifting Baseline Syndrome amongst the general public is unfortunately likely to lead to increased tolerance for a degraded environment, as well as exacerbated general environmental unawareness. There have also been concerns about what this might mean for decision makers and the ambition of their recovery targets for nature. For example, attempting to maintain or slightly enhance current levels of bio abundance would still mean accepting numbers of insects, birds and mammals that would seem shockingly low to our grandparents. An example of current policymakers’ lack of ambition on this front, and The Wildlife Trusts’ response to it, is here.

Researchers have more recently started trying to look at this phenomenon with more empirical methods, trying to put numbers on the psychology. One good piece of news is that a 2021 study found that although the general public’s perceptions are impacted (reliant as they are on memories rather than historical data and other longer-term analysis), there wasn’t a significant impact on conservation professionals and managers (who dig a little deeper). More work definitely needs to be done, but this is a promising sign that shifting baseline syndrome might just be an undercurrent rather than something which majorly influences the way conservationists set restoration targets.