Thanks to systematic biological recording and casual observations, we have plenty of historic data on the occurrence and abundance of butterfly species in Surrey. How can we use this rich resource to better understand the state of Surrey’s nature and guide conservation action, and what should we bear in mind when interpreting the data? Alisha Stafford-Jones analysed over 15,000 records for five butterfly species, seeking to find out what these records can tell us about the changing fortunes of these species, and what lessons can be drawn from this dataset to get the best value from future monitoring and recording efforts.

Butterflies, biodiversity and bio-abundance

As a part of my Masters in Environmental Science at the University of Southampton, I was tasked with completing a project in partnership with an external organisation to develop my work-based learning skills. I instantly turned to the Surrey Wildlife Trust as I have grown up enjoying the wide range of reserves they manage and have a great love for the conservation work they carry out.

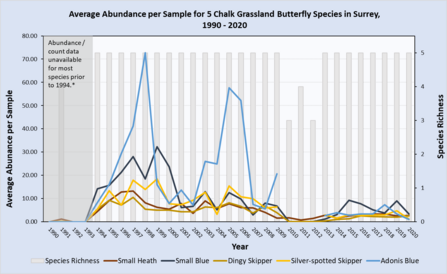

The project brief was very open, based around the idea of exploring the relationship between biodiversity and bio-abundance, which allowed me to decide on a target species and plan how best to investigate these trends. With the help of my project supervisor, I focused on five different butterfly species, looking at butterfly sampling data from 1990 to 2020 across Surrey Wildlife Trust reserves, provided by the Surrey Biodiversity Information Centre. To explore the different aspects of biodiversity, I made plots detailing species richness (the number of species present), species abundance per sample (the number of individuals present per sample), and species evenness (the relative abundance of each species) each year. I then focused on four nearby reserves in Surrey, using the butterfly abundance data in combination with land use data to explore the potential influence of land use management on butterfly biodiversity.

Butterfly species included in the project: 1. Small Heath (© Wendy Carter); 2. Siliver-spotted Skipper (© Philip Precey); 3. Adonis Blue (© Colin Williams); 4. Small Blue (© Tom Hibbert); 5. Dingy Skipper (© Vaughan Matthews)

The species abundance graphs showed extensive declines in the abundance of all five species since 1990 across Surrey. It was interesting, however, to see that this decline in species abundance occurred without a decline in the number of species present (species richness): often, all species remained present, just at low abundances. This means that relying on species richness as a measure of biodiversity alone may allow declines in abundance, and therefore changes in species interactions, to go unnoticed. If a species is no longer present in high enough numbers to carry out their ecosystem services (for example, pollination), that will have negative impacts on ecosystem functioning. This suggests that it is vitally important to monitor species abundances to assess the health of the habitat and the ecosystem as a whole. Species abundance measures may serve as an early-warning system mapping out the gradual declines in population before any potential population crashes that only then would then be picked up by measures of species richness.

Chalk grassland butterfly abundance and species richness across Surrey between 1990 and 2020. Gaps in the line graph represent years where no data was available.

* The dataset contained very little abundance data for most species before 1994 (instead records only mentioned presence / absence of species, making them unsuitable for use in the analysis), so it was not possible to calculate average abundance per sample for most species in the period from 1990 to 1993.

My attempts to explore these measures on a smaller scale, however, were not as successful. Species abundance data on a smaller, reserve-level, scale was much less robust than the county-wide records - with many years having no data recorded. Moreover, land management data for these reserves was only available between 2013 and 2019, making it difficult to see the effect that land management was having on butterfly abundance and biodiversity. This led to one of the main takeaways from the project: a large constraint to the study revolved around the lack of long-term data regarding land management and species abundance, especially on a smaller scale. The data available on both a larger and smaller scale was often not standardised and so could not be used in the analysis. Access to long-term, detailed, datasets will be vital to future research and so this report emphasised the need for the collection of standardised data at regular time intervals and on a smaller scale. Surrey Wildlife Trust is in fact pioneering a new approach to data collection and habitat mapping though its Space4Nature project.

More standardised data will aid future land management decisions by providing comprehensive datasets on species richness and abundance for specific reserves, to highlight how populations respond to different management techniques. This information can then be used to improve the recovery of Surrey butterfly populations.

Overall, I have had a great experience completing a project with the Surrey Wildlife Trust. It was amazing to be given access to an extensive dataset to explore a project that I am passionate about whilst also being able to work with experts in the trust who gave valuable insight and supported me throughout.

I hope that the results of this project help to highlight the decline in UK butterfly species and improve understanding of how monitoring could be carried out to improve future land management.