Ben Siggery is GIS, Research and Monitoring Manager at SWT. He is also studying for a Practitioner Doctorate in Sustainability in the Centre for Environment and Sustainability at the University of Surrey, funded by the Space4Nature (S4N) project. Here he explains how the academic and professional aspects of his work fit together.

Bridging the divide

I’m now one year into my PhD, which aims to support S4N by providing a historic baseline against which we can assess the current state of the environment. In other words, I’m trying to determine how rich in life Surrey should be if it weren’t for the damage inflicted by human activity. This lies within a field of science known as palaeoecology, or the study of past ecosystems and environments.

As a Doctoral Practitioner, I want my research to benefit practising conservationists. This is because, while paleoecology has an impressive history, it can feel inaccessible. In my PhD I am exploring the barriers to integration in conservation, experimenting with ways to overcome them and providing guidelines for academics, so they can make their work more easily translatable into effective action on the ground.

Opening the door

The first thing I learnt was that a PhD requires a vast amount of reading! Before I could start my own practical research, I needed to know what had been done already, where the gaps are, and what’s achievable. I concluded that palaeoecology has a huge potential to support conservation but that there’s a clear disconnect between academics and professionals, and valuable information is often hidden in specialist journals. What’s more, research projects are regularly designed without the input of practising conservationists.

Compare this with medicine, which has well established and funded procedures for researchers to circulate information to practitioners. Through S4N we are attempting to emulate this culture of knowledge exchange. I’m submitting my research outputs to both academic and practitioner publications and looking at how we can reframe information that has already been published, but not widely read.

Primary research

In the second six months of my PhD, I published a study based on the responses of 153 conservation practitioners, and their familiarity with and attitudes to paleoecology. It revealed problems such as a lack of money and resources to carry out research, and poor communication with academia. However, I also identified potential solutions, including creating a centralised online database, more access to applied case studies, and better links to legislation and policy decisions.

The other recommendations to come out of the work are that academics should aim to use examples that are relevant to practitioners, co-author with experts from NGOs, provide open access to published findings, and write summaries in simple English.

Palaeoecology in action

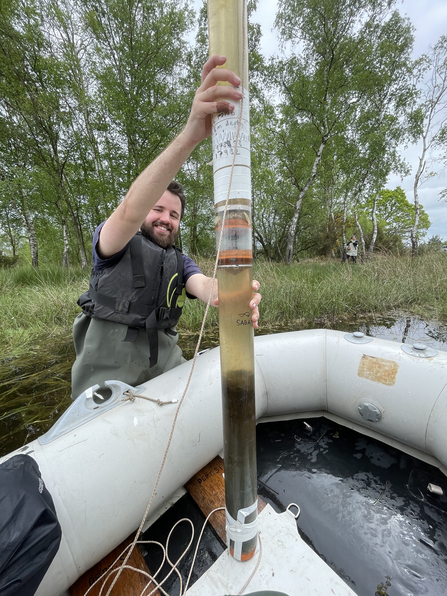

After a lot of time in the library and at the computer, my first outing in the field was to Chobham Common. Researchers from University College London and I collected two sediment cores from ponds that have existed on the Common for hundreds of years. We pushed a long tube as deep as possible into the sediment at the bottom of the pond and extracted a sample. We then cut and bagged 1cm slices for laboratory analysis of four indicators of environmental change:

-

Diatoms, a type of microscopic algae that only survive in very narrow ecological niches. Through them we can examine a range of variables, such as pH, water temperature, and salinity.

-

Spheroidal carbonaceous particles (SCPs) are only produced by burning fossil fuels. Their first (oldest) occurrence in a sediment core will coincide with the industrial revolution. Increase over time can also indicate the impact of periods such as the 1950s, where there was a dramatic increase in the use of fossil fuels.

-

Macrofossils, which are usually the remains of plants and invertebrates, can tell us about the local ecology and species assemblages of the area over time.

-

Macro-charcoal remains tell us about the frequency and intensity of wildfires over the history of the site.

Work to do

This summer the preliminary test results should begin to reveal some of the history of Chobham Common. In due course we will see what impact our findings may have on assumptions such as SSSI designations, and whether they inform our future heathland management strategies.

Meanwhile, I will be focusing on developing another case study with our Natural Flood Management Project at Wishmoor Stream. I’ll also be experimenting with ways to improve the accessibility of palaeoecology for conservation practitioners, through approaches like “recycling” existing data and looking into whether cost-effective, lower resource studies can still provide the necessary level of information for conservation work.

It looks like another busy year!